Is Mexico's experiment with democracy over?

I started this blog to write about France, and I mostly will, but I'm just back from a long trip to Mexico with some thoughts I'd like to share, so allow me a little ellipsis.

Mexico goes to the polls for a new president on July 1st, in the midst of a security situation so dire I hardly need to tell you - at least 20 thousand narcotrafficking-related deaths in five years, ingrained corruption so deep sections of the army and police force are fighting drug gangs' battles for them, perhaps half the country (mostly in the north) a virtual no-go zone where trafficking gangs have more power and command more loyalty than the government.

Amid widespread cynicism about the likelihood of a change of president doing anything to alter this, it's hard to remember that just 12 years ago Mexico celebrated what was billed as its first free and fair presidential election, lauded around the world as a transition to democracy. The Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) handed over power to historic opponents the National Action Party (PAN), after seven decades of often repressive one-party rule, and that was meant to change everything. Twelve years on, things look so bleak polls show the PRI set to return to power, just seven years after being forced out in disgrace, as Mexicans start to see multiparty democracy itself as a mistake. How did we get here?

The PRI always ruled through a highly centralised, corporativist system that gave them tight control of every sector of society, but especially the rural poor. By providing them with land, infrastructure like paved roads and electricity, and free health and education (usually poor and patchy services, often inaccessible or virtually non-existent, but still better than nothing) they expected unswavering electoral loyalty. Local politicians and landowners would ensure the inhabitants voted in the correct way, and threaten them with expulsion from their land or worse if they did not. They did resort to classic dictatorship tactics when opposition voices got too loud - torture, disappearance, burning villages - but they mostly held on through a mix of people's fear and resignation.

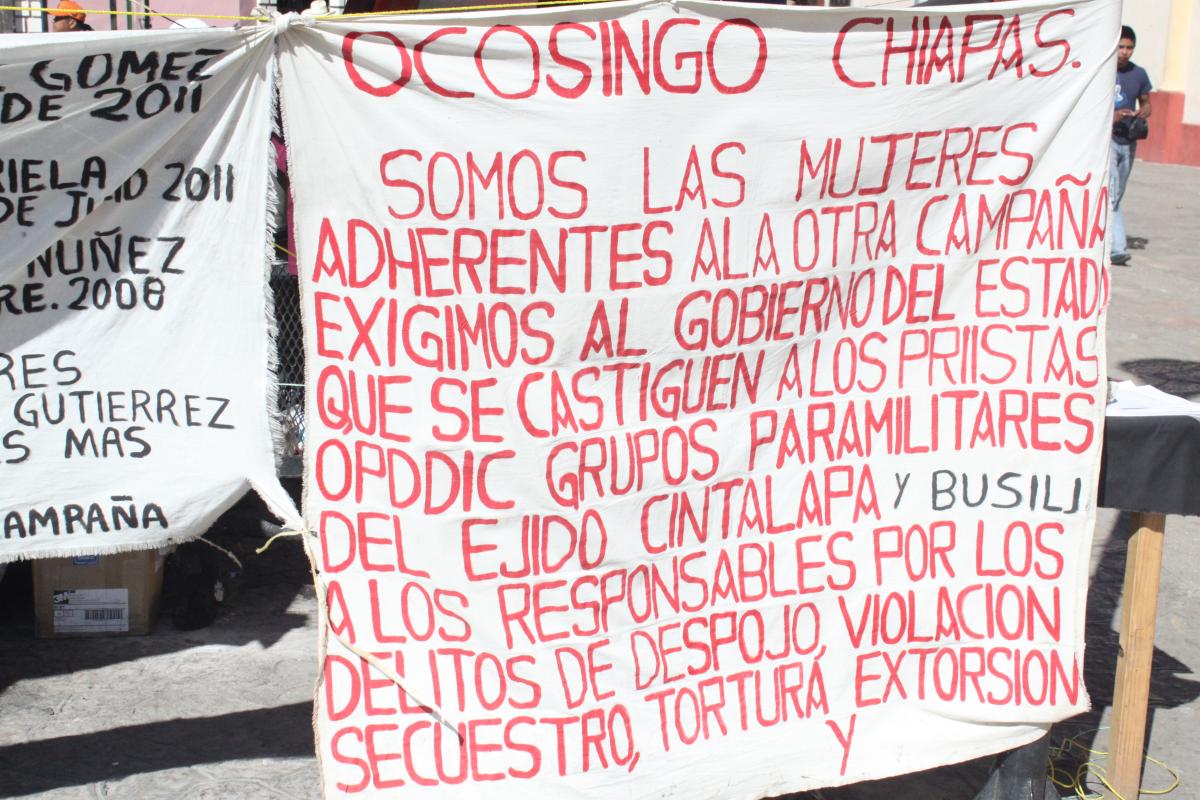

The PAN has a very different electoral base - the newly rich middle classes who drive Hummers and send their children to private universities in the US, and aren't afraid to deride the rural poor as uneducated 'Indians' - but their tactics in winning over poorer voters have shown a familiar mix of bribery and intimidation. They have also presided over a catalogue of human rights abuses as egregious as anything the PRI did - these get far less international coverage than the drug story, but hundreds have died. The best reported have been the 2006 massacre of protesters - angry local street sellers who had been banned from a municipal market in San Salvador Atenco near Mexico City - and the harsh police response to the six month long teachers' strike in Oaxaca in the same year (dozens of teachers and activists were killed when the army opened fire on demonstrators), but there have been many others. Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch both put Mexico as Latin America's worst human rights offender - and they report the state is using the 'war on drugs' as cover to suppress dissent, especially in Chiapas near the Guatemalan border, which is both a hive of trafficking activity and the home base of the Zapatista movement.

The Zapatistas' five municipalities are run autonomously, rejecting all interference from the federal government, and when I visited last week reisdents had plenty of stories of being repeatedly stopped, searched and beaten by troops claiming to be looking for drugs, and armed incursions into the villages themselves, with soldiers burning the houses and killing livestock. The PAN is not responsible for all this - in many parts of the country, the PRI control over the campesinos was never broken, and it is PRI local governors and officials who mete out the same punishments for dissent that they have always done.

That is partly why they are set to return to power. The other reason is that the collapsing national security situation of the last 12 years has convinced many voters that not only has the PAN failed them, the whole idea of switching parties has been a mistake, and it would be better to have the country run with an iron fist than descending into utter chaos. The PRI candidate, Enrique Pena Nieto, is riding high in the polls despite being at least as good at generating mocking headlines as any US Republican - he recently could not name three books he had read when being interviewed at a literary festival, and his daughter was caught on tape referring to voters as plebs.

This might seem internationally unimportant - but Mexico matters. Aside from being the source of probably the world's biggest law and order problem (which can't be tackled in Europe and the US if it isn't tackled at the source) it is a big country and a big economy, in a very strategic location. We should be giving more international news space to this depressing state of affairs.

3 Comments

Post new comment